Episode Transcript

[00:00:02] Speaker A: The building was under construction and the footings were not placed properly. They started building the foundation walls on top of it. Got the news that we had to tear everything out. So he looked at me and said, look, you're about ready to leave your job. Why don't you come and build this building? So I thought about it probably for 30 seconds and said, I'm in.

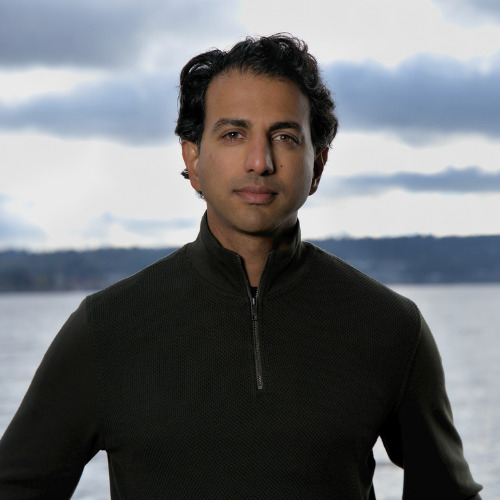

[00:00:27] Speaker B: This is dare to disrupt, a podcast about Penn State alumni who are innovators, entrepreneurs and leaders and the stories behind their success. I'm your host, Ryan Newman, and on the show today is Peter Coziello. Peter is the chairman, founder and CEO of Advanced Realty Investors, a company specializing in real estate development, construction and property management. Over decades of fluctuating market cycles, Peter led advance Realty to service major corporations with build to suit developments, including GH, Bass, Phillips, Van Heusen, Allied Beverage, FedEx, Bayer, and United National bank. Today, Advance Realty is one of the most active and respected commercial real estate development, investment and management companies in the northeast. Since its inception in 1979, advance has developed or acquired over 20 million commercial, residential, mixed use and industrial projects. Peter graduated from Penn State Smeal College of Business with a degree in finance.

Well, Peter, I'd like to welcome you to the Dare to disrupt podcast, and this is a first for us on the show. This is the first time we've had an entrepreneur in the real estate development and construction space, and we're excited to have you join us. Welcome to the podcast.

[00:01:51] Speaker A: Well, thank you. Thank you for having me, Peter.

[00:01:53] Speaker B: I'd like to get started as we always do, which is at the beginning. Could you share for our listeners where you grow up and what those early formative years were like in your early childhood?

[00:02:04] Speaker A: Well, I grew up in southwestern Pennsylvania, which was on the border of basically West Virginia, in a small town called Fairchance. Actually, it's a relevant name, you know, what happened here over the long term, but it was a very, very modest environment. It was in a coal mining town, about 2000 people, and unfortunately for my family, we were even on a position of being on public assistance. So we grew up in that kind of world. The schools were challenging at best. Throughout middle school we had outhouses. We didn't even have indoor running water and coal stoves and what have you. So it was a very humble environment growing up there, but certainly it had some good memories.

[00:02:47] Speaker B: We talk to people sometimes that are living in situations of poverty growing up, and some people have no awareness for it, while others had an acute awareness for it. Where would you say you were on that continuum of your awareness of the lack of resources that you had at.

[00:03:01] Speaker A: The family level, I didn't realize in totality, because there were a lot of people in my similar environment.

So when you're with, like, kind, you kind of don't pay attention to it. But I did know that we weren't doing so well. And I remember some of the, maybe when I got older, I remember some situations about being in surplus lines and getting food stamps and all that kind of stuff. So it did leave a mark, but I didn't realize it until I was older.

[00:03:32] Speaker B: You're coming from very, very humble means. How did the idea of college come into the picture? Was that always part of the picture or the future, or did it come later? And ultimately, how did you decide on where to go to school?

[00:03:43] Speaker A: Well, ultimately, what happened is that I was one of those kids that had a paper route. I worked. I didn't like this whole thing about not having any money. So I was always in that atmosphere. And then what occurred is I was in a serious auto accident when I was 15. Once I came out of the auto accident and got back to school, guidance counselor came down and said to me, you know that the state of Pennsylvania offers programs for rehabilitating people who may have been injured. Now, personally, I thought I was fully recovered, but in turn, she told me, why don't you go down to Pittsburgh, and you'll take these tests, and you may qualify for either technical school or whatever.

So I didn't pay a lot of attention. I did get on a bus. I went down to Pittsburgh. I took the test, and I came back, and a couple weeks later, she came up to see me. She said, you know something? You did really well on those tests. I said, what does that mean? She said, well, you know, the state of Pennsylvania will pay for you to go to college. Room, board, tuition, everything. And the problem then was I was in this high school environment where probably the top SAT score was about 950. Well, I was even below that. And it wasn't the fact that if I was dumb or other kids weren't dumb, was just the fact that we'd never seen this information before, never seen anything like this. We take those tests. So fortunately for me, I was able to get into a smaller school, southwestern Pennsylvania. And I was there for a couple of years, and I realized that it was a teacher's college was called then, and I was not going to be a teacher. I wanted to be in business because I really had a taste of making some money and doing things. So I knew that for me to be in business, I needed to go to a larger school, and that's where I was thinking about coming to Penn State. So I worked my butt off to get my grades up and finally got my grades up to a level where I could be accepted at Penn State.

[00:05:47] Speaker B: You talk about this, getting, this taste of business. I assume you're talking about the paper route. Can you just talk about some of the dynamics of the paper route and how that made you feel and why it kind of motivated or propelled you to want to actually pursue this sort of initial glimpse of what business could be like?

[00:06:04] Speaker A: You know, before the paper out, I used to go door to door selling Pb guy fifteen cents. I made four cents a copy. I was like eight years old. I remember at Christmas time, I'd crochet potholders, go door to door, sell them, I would do anything. So at the moment in time, whenever the opportunity came about to get a paper out, now, keep in mind I was twelve years old. Getting a paper out was a big decision, because now I had to get up at 530 in the morning. I remember I had 64 customers, and I made two cent a paper. So I made $1.28 a day, six days a week. You went around collecting your money on Saturdays, but I think having a paper out made me feel independent. The fact you were collecting $30 a week, pay my paper bill. They gave you a bill every Monday that you had to pay by Wednesday, and so it just gave you a sense of responsibility. And then on the other side, is coming from this poor, humble environment, I was able to buy things for myself that I couldn't buy, and I had steady income, and so that made me feel fulfilled. And I think it's an inspiration as.

[00:07:16] Speaker B: I went forward, also, paying the paper bill in many ways, is like meeting payroll as an entrepreneur, right? This obligation to actually pay money out of your pocket related to the cost of sales.

[00:07:26] Speaker A: I'm in the process of writing a book. And so with that, my writer asked me a lot of things. And over the weekend, I was looking through some papers about my paper route, and I remember that my mother had ledger sheets where he had rows of all the customers, how much money I collected from them, who owed money, how much I was going to spend on clothes, how much I had to put away for savings. And I thought to myself, oh, my God, think about this. At twelve years old, my mind was in that gear to start thinking about the accounting and posting of entries. Quite frankly, I didn't know what the hell it meant at that time. But now looking back on it, it definitely had some relevance to my thinking.

[00:08:11] Speaker B: Incredible. So you work to get your grades up, you find your way to Penn State. What was it like when you first arrived at Penn State?

[00:08:19] Speaker A: When I got to Penn State, keep in mind I probably never traveled more than 50 miles from where I grew up. So now I'm at Penn State and it's really a big change. And I remember I failed to every one of my exams. And I was like, scared. Thought to myself, this is not going to work out. Used to go to the library and I'd be there from 08:00 in the morning till seven at night. I just flipped pages, basically with tears running down my eyes, and how am I going to make this happen? So at the end of the day, what happened? I made a dean's list.

Then all of a sudden, I'm considered an honors student, you know, holy smoke. Now I've arrived, right? So that was my introduction to Penn State.

[00:09:04] Speaker B: As you start to head towards graduation, what are you thinking about? What are your initial career aspirations, and how did that play out for you?

[00:09:10] Speaker A: Well, what I found along the way is that I enjoyed and liked finance. And my whole dream at that moment was to go to Wall street.

And then when I graduated from Penn State, Wall street was under a thousand. I think the Dow actually went down about 500 in the early seventies, so there were really no jobs available. And at that point, I made a decision. Someone gave me some good advice. Go to work in a bank, because you'll learn a lot about financial transactions. And that's exactly what I did.

[00:09:41] Speaker B: And so you decide to find your way into banking. What was it like sort of stepping into that world?

[00:09:47] Speaker A: I enjoyed it very much, and I was a credit analyst. And so spreading financial statements, equipment, financing, and so you got to learn a lot about that area. And it was tremendous education that actually served me well for a lot of years, certainly.

[00:10:03] Speaker B: So you're getting this great education and credit and how a bank thinks about lending money to customers. And at what point did the thought cross your mind about maybe stepping out entrepreneurially and wanting to do something on your own?

[00:10:17] Speaker A: It was always there, because one of the things about being a banker, you see all the financial statements. So I got to see financial statements of a lot of privately held companies, big, small. And when you're a banker, you get to sit across some of these people and I could ask a lot of questions and they give me all the answers because I had something very valuable, money that they wanted to borrow. So from that standpoint, it was very educational. And that's kind of what led into, I had learned at that moment a lot about real estate investment trusts and reits and what we were doing at the bank. We were providing backup lines of credit against their issuance of commercial paper. How I really jumped into real estate was that one day the commercial paper market dried up, all the lines of credit got drawn down, and we weren't as smart as we should have been. And in turn, it created a big debacle. I had an opportunity to go to work with an advisory firm, and I loved real estate. It just enamored me. So I left to go to work advisory firm, and that was unbelievable education.

[00:11:28] Speaker B: Can you tell us more about what that experience was like?

[00:11:31] Speaker A: We're advisors to commercial banks in analyzing the portfolios of the real estate investment trust. And what happened is all the banks that lent it was, in essence, unsecured debt. They would do what they call exchanges. They would exchange the unsecured debt for assets on their books. So the banks really didn't have the expertise to go in and analyze all of these portfolios. So my job was I spent 50% of my time talking to commercial banks and about 50% of my time in the field, you know, looking at assets and trying to figure out what the next steps are. But this job was kind of crazy because I was traveling between three and 400,000 miles a year domestically. So it's not uncommon to go to the west coast twice in a week. So at first, coming from that fair chance, never traveled more than 50 miles. And I remember my first day on this job, I. I went to San Francisco. I was like, oh, my God, this is good. And that lasted for a while, but at the end of the day, it gets old.

[00:12:37] Speaker B: But at first, I mean, your eyes must have widened when the first time you flew out to California and saw how different it was. And you're doing this advisory work. And so from there, what led you to ultimately start your own company?

[00:12:48] Speaker A: Well, doing this advisory work was laborious, traveling 3400,000 miles a year, and I realized that this is no life. So I made the decision that I'm out of this at that point. ThAt's when I made the jump to start advance.

And advance is one of those stories that gets started with $5,000. Wow. So in the process, I realized that being a developer would be the best leverage I could have because I couldn't afford to buy existing buildings. I didn't have a down payment, but I did could make a deposit on a piece of land, and then if I could get all the developmental approvals, I'd be in a position to increase value. So if I could increase the value, then in turn I could get financing. I made a $5,000 deposit on a piece of land. I think the contract was like 85,000. I had no way that I could close on the property, but I just figured I'd figure it out. Someone I met at the bank, a customer. He was in the Midas Muffler business, so he had stores, and when I met him, he had three stores. So I became his confidant and I showed him how to buy them and be able to finance them 100%. He needed office space, so he said, look, why don't I become your partner? He became my partner in this office building, and when he did that, that he took about 7000 space. It's a 14,000 foot building.

Now here's where it gets a little tricky, is that we hired a friend of his who was the contractor, and that contractor, in turn, had some health issues and ended up having a heart attack. The building was under construction and the footings were not placed properly. So we're about in the middle of winter. They started building the walls, foundation walls on top of it. Got the news that we had to tear everything out. So he looked at me and said, look, you're about ready to leave your job. Why don't you come and build this building? So I thought about it probably for 30 seconds and said, I'm in. This building gets built. It ended up that my cash flow from the building was $9,000 plus a $5,000 management fee. So I was making $14,000 a year. And I said to myself, you know what? I don't care how much pain this is. If I could do this ten times, I could be making almost $150,000 a year. And by the way, in 1979, $150,000 a year was a lot of money. That was the start of advance.

[00:15:23] Speaker B: So you're learning on the fly. You've got one building done, you've got positive cash flow from that building, but still very hard to go to the bank and say, now give me a loan for a second building. How did you, before you sort of achieve scale, how did you move from that first project then onto the second?

[00:15:38] Speaker A: Well, the second project is interesting because I knew some developers who had some financial issues. They had an office building with two apartments upstairs. They needed cash, and so I made a deal to buy the building for 140,000 then I went in and restructured the leases, and I got the bank to lend me 150,000.

So at day of closing, I got $10,000 of, quote unquote, free money. And what happened was I went ahead and modernized the apartments. And so this became relatively lucrative for me because I was living in that apartment for free.

And it was a large apartment. So I actually had my office inside the apartment. So basically, I ended up in a situation where I had zero or very low overhead.

[00:16:32] Speaker B: Incredible people that want to get into real estate and want to get into real estate development. Most people will say, well, I dont have any money to be able to do it for you. What was it that actually gave you the confidence to just start?

[00:16:43] Speaker A: I had the mental attitude that theres nothing thats a problem if you can work out of the problem. So, in essence, if you developed a skills, you can work through anything. I was in a position that, you know, this is something I really want to do. I had one building up that was successful. I had another building that I had purchased, then I had several others that I was going under contract. There was a moment in time that the prime rate was like 22, 23%. So I was paying like 24, 25% for money. And that was tough.

[00:17:17] Speaker B: Well, and the challenge is you didn't have any resources or capital. You didn't have another choice. It was borrow the money to be able to get the capital or not have the capital to be able to start the project.

[00:17:27] Speaker A: Right, right.

[00:17:28] Speaker B: Incredible.

[00:17:29] Speaker A: All the loans I was signing personally, it didn't really matter, because if it was going to blow up, it was all blowing up.

[00:17:37] Speaker B: There was nothing for the bank to come and take.

[00:17:39] Speaker A: No.

[00:17:39] Speaker B: And so as you started to advance in the business, no pun intended there, but as you started to advance in the business, how did you think about the different industry verticals of real estate and how you pursued each of those individual verticals?

[00:17:51] Speaker A: Well, I must tell you that probably the first five years of advance, I would do anything to survive, and anything meant that I mentioned this gentleman that owned the Midas muffler stores. I had a deal with him that every store that I would build, he would pay me $60,000, but I had to get to finance it. So there was a point in time. I was building three or four of those a year. And where my big breakthrough financially was that I went to one of these conventions home builders, and there was, they were talking about office condominiums, and I said, oh, my goodness, this. I can do this. And in turn, the first building that I came back and did. I made $600,000, and I was like, oh, man, this is a really a great idea. So then I remember I now had this money, and I was making down payments on another piece of land. And the next one I did, I made $1.2 million.

So then I kept on making down payments on other pieces of land with the idea that I know how to get these things financed and built, and I'll figure that out.

[00:19:03] Speaker B: What allowed for such a big margin on some of those early projects?

[00:19:06] Speaker A: It was just the fact that instead of selling a whole building, we were selling pieces as a condominium. In selling pieces, I was retailing the space. And what happened was it was more cost effective for a client to buy condominium than to rent office space. And then I convinced them you're building up equity and so forth. And we had done a lot of square footage like that, which then got into some of the first larger transactions of being able to do a build suit for a large corporate client.

[00:19:42] Speaker B: You talked about the fact that you were taking the profits from one project and rolling them into deposits on others, and you figured out how to get the financing done. Is it fair to say you also need an underlying market environment that's constructive both to financing and just to economic growth in general? I'm sure you've been through many market cycles. But in that early stage, where you're taking those initial profit winnings and deploying them in the form of deposits for new projects, were you also benefiting from a market timed cycle that was actually expansionary?

[00:20:15] Speaker A: At that time, I was benefiting. You're absolutely correct. What really happened here when interest rates were 24%, I knew in my mind that all these projects that I wanted to build was good real estate. The only problem was the interest rates were so high that the economics didn't work. So I was able to hold on to those properties as long as possible. And then when interest rates started to fall, then everything happened for me. Then I had some years where we were making substantial dollars. Because of that, I got to be in a good position where I arbitrage the risk.

So I was under contract, did not close market, then started to boom, interest rates started to fall down. And then I was in a position that I had a lot of built in equity in these projects going forward.

[00:21:10] Speaker B: What you're talking about here is because of the time delay of when you would sign up a project versus when you would close by virtue of rates coming down, the value of what you're closing on. Even though you've already preset. The price at one level is now literally going up as rates fall. Is that correct?

[00:21:26] Speaker A: That's correct.

Looking to stay up to date on Penn State's entrepreneurship scene, the invent Penn State monthly newsletter has it all, from inspiring student startup stories to outstanding research discoveries on the path to market. We cover the latest news and events. Don't miss out. Subscribe now. Visit invent psu.edu newsletter. That's invent psu.edu newsletter. Stay informed and connected with invent Penn state.

[00:22:01] Speaker B: Let's talk about some of these larger projects. You talked about how you shifted into build to suit projects. First of all, can you explain what the market of build to suit is and how you broke into that market?

[00:22:12] Speaker A: When I was contracting some of these land sites, there was a chemical company, large, significant, and they came to me about building a building on one of the land sites that I owned. What happened is that they owned a site that they built the lab. And I said, then why aren't you building your office building there? And the question was, well, our parent won't invest in an office building. So I said, that's no problem. I said, what if I just master lease from you a piece of ground? I'll build a building on your site. Actually, they agreed to that. And so I built that building. That building was almost 100,000. That was one of our first larger projects. From there, I understood a lot about build to suits and then I coined this idea about buy the suits. I was focused on calling on corporations and I would convince them that I could find locations for them and also have a building that would be more effective from a design standpoint, which I refer to designing them inside out. Then once that work was all done, my position was, if I can find a building in a marketplace that we can buy, that you can lease, we'll do that.

If in fact I can't, I'll do a build to suit for you. Build a suit means I'll build a building for you. So at that moment in time, I did buildings in Portland, Maine, for bass shoes, our corporate headquarters. I think it was like 120,000ft. We did Phil Saint Mews in New Jersey, which is 220,000ft. I did bank buildings, FedEx. So I really got onto this concept that propelled advanced to a whole other level.

[00:23:57] Speaker B: Incredible. And this concept of build a suit to buy the suit can delineate what the difference is.

[00:24:03] Speaker A: Build a suit is basically like having a custom suit, it's made perfectly for you, and a buy to suit is that I could find a building that was perfect for you and it was more cost effective than building from ground up.

[00:24:21] Speaker B: In many ways, what you were offering these businesses was a way to be asset light. You know, they're a core competency and specialty is not in real estate. It's whenever the product with which they're making is you're allowing them to basically lay these costs off their balance sheet and in theory, increase the return of equity on their primary core business while they offload this real estate asset to you. It's great for them because they get to be asset light, but for you, it also means that you are now laden with all these assets. So how did you navigate kind of having the responsibility and if not burden of owning all of this real estate and then still be able to make it profitable for you? How did that all sort of work?

[00:24:59] Speaker A: In some cases I brought on partners, in other cases I was able to get bank for the insight. The biggest problem was that I was personally guaranteeing all the debt.

So there was a point in time that I was on the hook for about quarter billion dollars worth of debt. And it's not a place you want to be as a developer because it's way too much risk to personally guarantee that much debt. And then I ultimately did what is known as an upREIt sale and sold to a public REIT and took back shares of stock.

[00:25:32] Speaker B: Interesting. In addition to running and building such a tremendous business with advanced realty, you've also been very philanthropic. In 2022, you announced a major gift to start the Kokosiello Institute of Real Estate Innovation at Penn State. Can you just talk to us a little bit about what the catalyst for you was in making that gift?

[00:25:51] Speaker A: Penn State is a treasure chest of knowledge and disciplines. Why can't we cross collaborate with all these other disciplines? Because when you talk to real estate developers, none of them major in real estate development. So if you take a look at all the disciplines, whether it's supply chain, whether it's engineering, whether it's architecture, I mean, just goes on and on. Like when you look at material sciences, I was amazed at material sciences and what's going on there and how they could really help the industry. So if you look at all this education is moving towards cross collaboration, it's no more that I'm going to say I can major in accounting and I'm going to have a job for the next 40 years of my life. Not going to happen. The ability to cross collaborate and bring all these silos together is in the forefront. And I think that is what got me excited, and hopefully everyone else as well.

[00:26:50] Speaker B: So it's important to note the word innovation is in the name of the institute. And it sounds like for you, innovation starts with this idea of cross disciplinary focus in terms of what the types of students and education you're trying to attract, I presume.

[00:27:05] Speaker A: Yes. Right now we're working on onshoring supply chain. It's moving out of China. How do you ensure it's moving into Mexico? Certainly when you look at robotics, it should be moving into Pennsylvania, because Pennsylvania can extract a lot of that gas, and you have a lot of energy, so you have the ability to produce manufacturing more broadly.

[00:27:26] Speaker B: How do you see technology playing a role in the evolution of real estate as an industry?

[00:27:32] Speaker A: Look at what Zoom has done to the real estate industry. Look what it did from the standpoint of remote workers. Look what it did to businesses. So there's a number of different things that are happening. The ability of working remotely after Covid or during COVID is really one of the strongest areas that disrupted certain office space. So from that standpoint, I think there are more disruptions to come. The office space needs to be amenitized, meaning that people want to be in office space. People like to go down and have a coffee, whether it's a Starbucks or what have you. People like to congregate. They don't need to be in one single office environment. So therefore, if you're building office space, you need to make sure it's highly amenitized, meaning a gym. It has food services, walkability, and that type of thing, where I see a huge, significant change. In fact, I was in a meeting yesterday. We're building some buildings that are 400 apartments each.

So we just finished one, and we learned a lot. And part of what we did is we have lack of better terminology. Weworks kind of facility inside, so there were 28 workstations with little offices where people can do zoom meetings, what have you. And so now in our next building, we're going to make it much bigger, because I see that companies actually may even pay us or pay employees to be able to work out of these facilities.

So you're seeing the overlap, mixing conversions of apartment buildings to be quasi workspace office buildings. Now, inside these apartment buildings, they have a lot of amenities. Swimming pools to restaurants, to big lobbies, open spaces. So it makes for a very nice way of working if you're working at home. And it reduces the footprint of the company with office space, because, like an I know user right now, that was in 200,000 sqft, they're going to take 100,000 sqft because they have this remote working that's going on. And inside these spaces, it's a higher density. So there's a lot of things like that. But I think that's one of the biggest ones. I think apartment buildings are going to become quasi office buildings.

[00:30:06] Speaker B: So when you look at all that advanced realty has done and created, what do you think the young boy from fair chance, Pennsylvania would have thought about where it's ended up? Where you are today?

[00:30:16] Speaker A: You know, I'm excited. It's like a dream come true. I'm getting older now, but I still think I'm fairly astute at this game. And actually it's gotten much easier because if you believe in continuous education, you believe in staying relevant. I'm still doing that every day, reading a bunch. And so I can make a lot of really good choices. So being able to make the choices and to do something like I'm doing here at Penn State with this innovation institute of real Estate is rewarding. And so it's a lot of fun. So it's not as much work when I used to sign personally on. All those loans come a long way.

[00:30:57] Speaker B: Well, thank you, Peter, for taking the time today to share your entrepreneurial journey with me. I'd now like to hand things over to a current Penn State student, John Smith. John is a junior at Penn State studying architectural engineering. He's also the co founder and CEO of Streamlined Charging, which builds electric vehicle charging stations that make financial sense for apartment owners. He recently participated in the Advent Penn State Summer Founders program, which provides each student startup with a $15,000 grant to work on their startups over the summer. John, I'll now hand the interview over to you.

[00:31:34] Speaker C: Awesome. Thank you so much.

[00:31:35] Speaker A: Ryan. Hi, John. Nice to meet you.

[00:31:37] Speaker C: Nice to meet you, Peter. In my time talking with state college property owners, I've seen many very confused about EV infrastructure. Even though they see the need, they're often very hesitant to actually install these stations. I know you were talking a lot about amenities before. Do you have any insight into how new amenities are adopted in the real estate market?

[00:31:56] Speaker A: Yeah. So most of our buildings that we're building apartments and even some of the office buildings we still have, we put in charging stations.

So we have been working with the company that has these high speed chargers, and, you know, it's a ratio. We don't put in one to one for parking space, but some of these garages are typically anywhere from 200 to 300 cars. So in turn, there might be 30 of these charging stations. And so from that standpoint, it can become a profit center for us. And it's something that amenity that. I don't know how you build a building without it, quite frankly. It's just you have to have it because there's a whole population that wants to have this green movement. And so if you're not making that statement, hey, we're green, we're trying to reduce our carbon footprint. If you have a battery operated car, you discharge. Yeah.

[00:32:52] Speaker C: So I'm nearing the end of my undergraduate degree, and I'm going to be starting a PhD in architectural engineering and material science soon. Oftentimes, mixing like an entrepreneur narrow mindset with an academic one is challenging. What advice do you have for people starting out in academia in order to make sure their research is aligning with what industry really needs?

[00:33:12] Speaker A: Well, I think part of it is to watch what we're doing because we have an advisory board of some leaders in a real estate industry. What our focuses are would kind of dictate what, in fact is necessary from an educational standpoint. So our ability, we're trying to drill down in these schools. So to give you some ideas, I think the whole world of concrete is only at its infant stage. This whole world of 3d printing, the ability to build buildings from 3d printing, to use concrete, and concrete being a material that can be recycled. And I think you're going to see houses being built out of concrete, 3d printing, and they could build houses in probably 45 days. So that's interesting. The other area, I think, is glass. I think there's a lot of research with glass. I think that the next area that is going to be significant, and we're trying to work on this as well. Penn State has a huge initiative that has to do with nuclear energy. You know, the carbon footprint of these buildings is critical to truly analyze. And then if you can create buildings without consuming any energy, that's a win for everyone. And that's proven to be very expensive with that scenario. But then you're talking about all these recyclable materials, like exploring now that looks like wood and it's not. So you're going to see a lot of that innovation and so forth. But I think part of it is also designs and so designs of these buildings and how they hold energy and how they discharge the heat or cooling, depending upon the circumstance, it's going to become critical. So you're in for a joyride.

[00:35:00] Speaker C: It's funny, my lab basically is working on recycling concrete and 3d printing concrete. With a lot of these technologies we're developing, there's a long list of regulations we have to work around, such as code adoption. Do you have any insight? Do you feel that there are large regulatory barriers holding back innovation in industry?

[00:35:18] Speaker A: I think there are some areas that's holding it back, but I think there's other areas that it's being welcomed.

And so what's welcomed is sustainability, recycling, materials, mechanical engineering. Some of these systems that are in buildings now are very, very efficient compared to what they were before. Awesome.

[00:35:38] Speaker C: Thanks so much, Peter.

[00:35:39] Speaker A: You're welcome.

[00:35:42] Speaker B: That was Peter Krakoziello, chairman, founder and CEO of Advance Realty Investors. This episode was produced and edited by our executive producer Katie D. Fiore. If you haven't already, be sure to subscribe to dare to disrupt wherever you listen to podcasts and look out for next month's episode. Thanks for listening.